Rob Calvert Jump and Jo Michell

In August 2022, revisions to official measures of UK output generated headlines because the new figures implied that the economic contraction during the pandemic was greater than previously thought.

At the same time, however, substantial revisions were made to historical data, and these received far less attention. One outcome of these revisions is that the UK’s performance relative to other rich economies during the austerity period of 2010–2016 has been downgraded: growth in real GDP per capita over this period is now meaningfully lower. This means that some recent analyses relying on the older figures are misleading.

For example, in a recent FT article, Chris Giles includes data showing that the UK had the highest growth of real GDP per head in the G7 between 2010 and 2016. Inevitably, the article was circulated by defenders of austerity including Rupert Harrison and Tim Pitt, alongside a claim that the data “shows why the idea austerity has caused our growth problems post-GFC doesn’t stack up. During peak austerity (2010-6) UK had strongest GDP per capita growth in G7”.

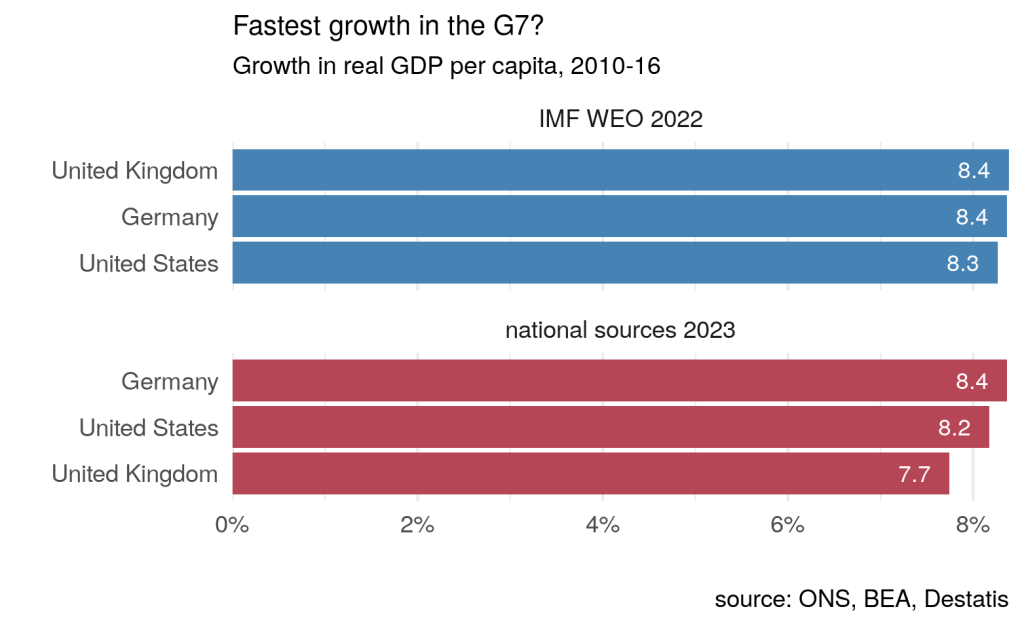

The data used by Chris Giles are from the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) October 2022 World Economic Outlook (WEO), and show average annual growth in real GDP per head of 1.4% in the UK between 2010 and 2016, compared with 1.3% in both Germany and the USA. But the October 2022 WEO uses data from the 2021 Blue Book, which were compiled before the most recent set of revisions were introduced.

The 2021 data imply that total per capita growth between 2010 and 2016 was 8.39% in the UK, compared with 8.36% in Germany and 8.27% in the USA. On these numbers, the UK is indeed the highest, albeit by a margin in the second decimal place: under a billion pounds separates the UK and Germany. (This very slim margin appears larger in the FT chart due to growth rates being annualised and then rounded to 1 decimal place, implying UK growth of 8.7% versus German growth of 8.1%, a difference of 0.6 percentage points rather than the actual difference in the IMF data of 0.03 percentage points.)

However, according to the revised figures, real per capita growth in the UK over this period was only 7.7%: total nominal GDP growth between 2010 and 2016 was revised down by around one percentage point in the 2022 data, culminating in lower cash GDP of around £17 billion by 2016. Smaller adjustments to inflation estimates mean that real GDP growth was revised down by around 0.7 percentage points, from 13.4% to 12.7%. Alongside unchanged population estimates, the result is that official real GDP per capita was revised down by around £340 (in 2019 prices) by 2016 – an amount approximately equal to a third of the average household energy bill in that year.

These revisions are summarised by the ONS here, and their sources are discussed here. The bulk of the revisions are due to the contribution of the insurance industry to GDP being revised down by the use of Solvency II regulatory data, as well as improvements to the way pension schemes are measured. In addition, and of particular relevance for the current exercise, part of the revisions are due to the ONS, “bringing through a package of sources and methods changes that improve the international comparability of the UK gross domestic product (GDP) estimates.”

These revisions make a material difference to UK GDP, as well as its international ranking. On the basis of the latest official figures taken directly from national statistical agencies, real UK per capita growth of 7.7% during the austerity period compares with 8.4% for Germany and 8.2% for the US.

So, based on the most recent data, the UK did not have the fastest growth in GDP per capita between 2010 and 2016.

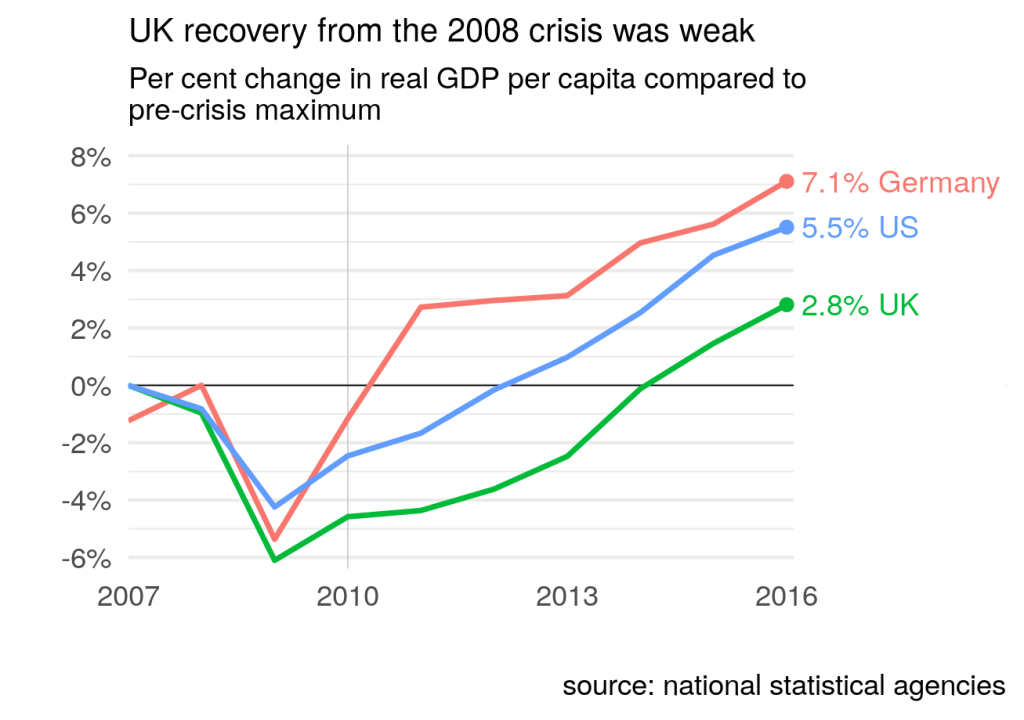

Aside from this, as others have noted, focusing narrowly on the 2010-2016 period is potentially misleading. When austerity was implemented, the UK was in the process of recovering from the 2008 recession. It is likely that there was substantial spare capacity which, under strong demand conditions, could have been quickly reabsorbed into economic activity. If we start our comparison at the pre-crisis peak (2007 for the UK and US, 2008 for Germany), rather than 2010, the divergence is much greater: by 2016, real UK GDP per capita had increased by 2.8% on its pre-crisis level, compared with 5.5% for the US and 7.1% for Germany. Much of UK growth during between 2010 and 2016 was recovering losses from the recession: GDP per capita did not reach pre-2008 levels until 2014, compared to 2011 for Germany and 2012 for the US.

As Chris Giles notes, “Most economists now accept that the sharp reductions in public spending between 2010 and 2015 delayed the recovery from the financial crisis”. Comparing outcomes with pre-crisis levels is not, therefore, “baseline bingo” as claimed by Rupert Harrison. These outcomes are hard to square with Harrison’s claim that this is “what catch up looks like”.

These data revisions highlight the dangers in drawing strong conclusions – particularly about politically loaded topics – from small differences in data that are subject to measurement error and revision. It is inevitable that an FT article claiming that UK growth per head was highest in the G7 during the main austerity years will be used as justification for austerity policies. But, on the basis of the most recent and accurate data available, the claim is false. UK GDP growth was relatively strong by international standards (and may yet be revised back to the top of the table) but this statement ought to be placed in its proper context, using a variety of data sources and an understanding of their strengths and weaknesses.

| Nominal GDP (YBHA) | Real GDP (ABMI) | ||||

| Year | 2021 Blue Book | 2022 Blue Book | 2021 Blue Book | 2022 Blue Book | IMF 2022 WEO |

| 2010 | 1,612,195 | 1,612,381 | 1,884,515 | 1,876,058 | 1,884,515 |

| 2011 | 1,669,509 | 1,664,211 | 1,911,983 | 1,896,087 | 1,911,983 |

| 2012 | 1,721,355 | 1,713,241 | 1,940,087 | 1,923,551 | 1,940,087 |

| 2013 | 1,793,155 | 1,782,296 | 1,976,755 | 1,958,557 | 1,976,755 |

| 2014 | 1,876,162 | 1,862,827 | 2,035,883 | 2,021,225 | 2,035,883 |

| 2015 | 1,935,212 | 1,920,998 | 2,089,276 | 2,069,595 | 2,089,276 |

| 2016 | 2,016,638 | 1,999,461 | 2,136,566 | 2,114,406 | 2,136,566 |

Data are in millions of pounds (2019 pounds for the real data). Data downloaded from ONS and IMF websites on 20th March 2023. Note that the 2022 Blue Book dataset was only published on the 31st October 2022, too late for inclusion in the IMF’s October 2022 World Economic Outlook. The revisions were initially introduced (and reported on) in August 2022, the quarter before the Blue Book publication.