So the post-mortem begins. Much electronic ink has already been spilled and predictable fault lines have emerged. Debate rages in particular on the question of whether Trump’s victory was driven by economic factors. Like Duncan Weldon, I think Torsten Bell gets it about right – economics is an essential part of the story even if the complete picture is more complex.

Neoliberalism is a word I usually try to avoid. It’s often used by people on the left as an easy catch-all to avoid engaging with difficult issues. Broadly speaking, however, it provides a short-hand for the policy status quo over the last thirty years or so: free movement of goods, labour and capital, fiscal conservatism, rules-based monetary policy, deregulated finance and a preference for supply-side measures in the labour market.

Some will argue this consensus has nothing to with the rise of far-right populism. I disagree. Both economics and economic policy have brought us here.

But to what extent has academic economics provided the basis for neoliberal policy? The question had been in my mind even before the Trump and Brexit votes. A few months back, Duncan Weldon posed the question, ‘whatever happened to deficit bias?’ In my view, the responses at the time missed the mark. More recently, Ann Pettifor and Simon Wren Lewis have been discussing the relationship between ideology, economics and fiscal austerity.

I have great respect for Simon – especially his efforts to combat the false media narratives around austerity. But I don’t think he gets it right on economics and ideology. His argument is that in a standard model – a sticky-price DSGE system – fiscal policy should be used when nominal rates are at the zero lower bound. Post-2008 austerity policies are therefore at odds with the academic consensus.

This is correct in simple terms, but I think misses the bigger picture of what academic economics has been saying for the last 30 years. To explain, I need to recap some history.

Fiscal policy as a macroeconomic management tool is associated with the ideas of Keynes. Against the academic consensus of his day, he argued that the economy could get stuck in periods of demand deficiency characterised by persistent involuntary unemployment. The monetarist counter-attack was led by Milton Friedman – who denied this possibility. In the long run, he argued, the economy has a ‘natural’ rate of unemployment to which it will gravitate automatically (the mechanism still remains to be explained). Any attempt to use activist fiscal or monetary policy to reduce unemployment below this natural rate will only lead to higher inflation. This led to the bitter disputes of the 1960s and 70s between Keynesians and Monetarists. The Monetarists emerged as victors – at least in the eyes of the orthodoxy – with the inflationary crises of the 1970s. This marks the beginning of the end for fiscal policy in the history of macroeconomics.

In Friedman’s world, short-term macro policy could be justified in a deflationary situation as a way to help the economy back to its ‘natural’ state. But, for Friedman, macro policy means monetary policy. In line with the doctrine that the consumer always knows best, government spending was proscribed as distortionary and inefficient. For Friedman, the correct policy response to deflation is a temporary increase in the rate of growth of the money supply.

It’s hard to view Milton Friedman’s campaign against Keynes as disconnected from ideological influence. Friedman’s role in the Mont Pelerin society is well documented. This group of economic liberals, led by Friedrich von Hayek, formed after World War II with the purpose of opposing the move towards collectivism of which Keynes was a leading figure. For a time at least, the group adopted the term ‘neoliberal’ to describe their political philosophy. This was an international group of economists whose express purpose was to influence politics and politicians – and they were successful.

Hayek’s thesis – which acquires a certain irony in light of Trump’s ascent – was that collectivism inevitably leads to authoritarianism and fascism. Friedman’s Chicago economics department formed one point in a triangular alliance with Lionel Robbins’ LSE in London, and Hayek’s fellow Austrians in Vienna. While in the 1930s, Friedman had expressed support for the New Deal, by the 1950s he had swung sharply in the direction of economic liberalism. As Brad Delong puts it:

by the early 1950s, his respect for even the possibility of government action was gone. His grudging approval of the New Deal was gone, too: Those elements that weren’t positively destructive were ineffective, diverting attention from what Friedman now believed would have cured the Great Depression, a substantial expansion of the money supply. The New Deal, Friedman concluded, had been ‘the wrong cure for the wrong disease.’

While Friedman never produced a complete formal model to describe his macroeconomic vision, his successor at Chicago, Robert Lucas did – the New Classical model. (He also successfully destroyed the Keynesian structural econometric modelling tradition with his ‘Lucas critique’.) Lucas’ New Classical colleagues followed in his footsteps, constructing an even more extreme version of the model: the so-called Real Business Cycle model. This simply assumes a world in which all markets work perfectly all of the time, and the single infinitely lived representative agent, on average, correctly predicts the future.

This is the origin of the ‘policy ineffectiveness hypothesis’ – in such a world, government becomes completely impotent. Any attempt at deficit spending will be exactly matched by a corresponding reduction in private spending – the so-called Ricardian Equivalence hypothesis. Fiscal policy has no effect on output and employment. Even monetary policy becomes totally ineffective: if the central bank chooses to loosen monetary policy, the representative agent instantly and correctly predicts higher inflation and adjusts her behaviour accordingly.

This vision, emerging from a leading centre of conservative thought, is still regarded by the academic economics community as a major scientific step forward. Simon describes it as `a progressive research programme’.

What does all this have to with the current status quo? The answer is that this model – with one single modification – is the ‘standard model’ which Simon and others point to when they argue that economics has no ideological bias. The modification is that prices in the goods market are slow to adjust to changes in demand. As a result, Milton Friedman’s result that policy is effective in the short run is restored. The only substantial difference to Friedman’s model is that the policy tool is the rate of interest, not the money supply. In a deflationary situation, the central bank should cut the nominal interest rate to raise demand and assist the automatic but sluggish transition back to the `natural’ rate of unemployment.

So what of Duncan’s question: what happened to deficit bias? – this refers to the assertion in economics textbooks that there will always be a tendency for governments to allow deficits to increase. The answer is that it was written out of the textbooks decades ago – because it is simply taken as given that fiscal policy is not the correct tool.

To check this, I went to our university library and looked through a selection of macroeconomics textbooks. Mankiw’s ‘Macroeconomics’ is probably the mostly widely used. I examined the 2007 edition – published just before the financial crisis. The chapter on ‘Stabilisation Policy’ dispenses with fiscal policy in half a page – a case study of Romer’s critique of Keynes is presented under the heading ‘Is the Stabilization of the Economy a Figment of the Data?’ The rest of the chapter focuses on monetary policy: time inconsistency, interest rate rules and central bank independence. The only appearance of the liquidity trap and the zero lower bound is in another half-page box, but fiscal policy doesn’t get a mention.

The post-crisis twelfth edition of Robert Gordon’s textbook does include a chapter on fiscal policy – entitled `The Government Budget, the Government Debt and the Limitations of Fiscal Policy’. While Gordon acknowledges that fiscal policy is an option during strongly deflationary periods when interest rates are at the zero lower bound, most of the chapter is concerned with the crowding out of private investment, the dangers of government debt and the conditions under which governments become insolvent. Of the textbooks I examined, only Blanchard’s contained anything resembling a balanced discussion of fiscal policy.

So, in Duncan’s words, governments are ‘flying a two engined plane but choosing to use only one motor’ not just because of media bias, an ill-informed public and misguided politicians – Simon’s explanation – but because they are doing what the macro textbooks tell them to do.

The reason is that the standard New Keynesian model is not a Keynesian model at all – it is a monetarist model. Aside from the mathematical sophistication, it is all but indistinguishable from Milton Friedman’s ideologically-driven description of the macroeconomy. In particular, Milton Friedman’s prohibition of fiscal policy is retained with – in more recent years – a caveat about the zero-lower bound (Simon makes essentially the same point about fiscal policy here).

It’s therefore odd that when Simon discusses the relationship between ideology and economics he chooses to draw a dividing line between those who use a sticky-price New Keynesian DSGE model and those who use a flexible-price New Classical version. The beliefs of the latter group are, Simon suggests, ideological, while those of the former group are based on ideology-free science. This strikes me as arbitrary. Simon’s justification is that, despite the evidence, the RBC model denies the possibility of involuntary unemployment. But the sticky-price version – which denies any role for inequality, finance, money, banking, liquidity, default, long-run unemployment, the use of fiscal policy away from the ZLB, supply-side hysteresis effects and plenty else besides – is acceptable. He even goes so far as to say ‘I have no problem seeing the RBC model as a flex-price NK model’ – even the RBC model is non-ideological so long as the hierarchical framing is right.

Even Simon’s key distinction – the New Keynesian model allows for involuntary unemployment – is open to question. Keynes’ definition of involuntary unemployment is that there exist people willing and able to work at the going wage who are unable to find employment. On this definition the New Keynesian model falls short – in the face of a short-run demand shortage caused by sticky prices the representative agent simply selects a new optimal labour supply. Workers are never off their labour supply curve. In the Smets Wouters model – a very widely used New Keynesian DSGE model – the labour market is described as follows: ‘household j chooses hours worked Lt(j)’. It is hard to reconcile involuntary unemployment with households choosing how much labour they supply.

What of the position taken by the profession in the wake of 2008? Reinhart and Rogoff’s contribution is by now infamous. Ann also draws attention to the 2010 letter signed by 20 top-ranking economists – including Rogoff – demanding austerity in the UK. Simon argues that Ann overlooks the fact that ‘58 equally notable economists signed a response arguing the 20 were wrong’.

It is difficult to agree that the signatories to the response letter, organised by Lord Skidelsky, are ‘equally notable’. Many are heterodox economists – critics of standard macroeconomics. Those mainstream economists on the list hold positions at lower-ranking institutions than the 20. I know many of the 58 personally – I know none of the 20. Simon notes:

Of course those that signed the first letter, and in particular Ken Rogoff, turned out to be a more prominent voice in the subsequent debate, but that is because he supported what policymakers were doing. He was mostly useful rather than influential.

For Simon, causality is unidirectional: policy-makers cherry-pick academic economics to fit their purpose but economists have no influence on policy. This seems implausible. It is undoubtedly true that pro-austerity economists provided useful cover for small-state ideologues like George Osborne. But the parallels between policy and academia are too strong for the causality to be unidirectional.

Osborne’s small state ideology is a descendent of Thatcherism – the point when neoliberalism first replaced Keynesianism. Is it purely coincidence that the 1980s was also the high-point for extreme free market Chicago economics such as Real Business Cycle models?

The parallel between policy and academia continues with the emergence of the sticky-price New Keynesian version as the ‘standard’ model in the 90s alongside the shift to the third way of Blair and Clinton. Blairism represents a modified, less extreme, version of Thatcherism. The all-out assault on workers and the social safety net was replaced with ‘workfare’ and ‘flexicurity’.

A similar story can be told for international trade, as laid out in this excellent piece by Martin Sandbu. In the 1990s, just as the ‘heyday of global trade integration was getting underway’, economists were busy making the case that globalisation had no negative implications for employment or inequality in rich nations. To do this, they came up with the ‘skill-biased technological change’ (SBTC) hypothesis. This states that as technology advances and the potential for automation grows, the demand for high-skilled labour increases. This introduces the hitch that higher educational standards are required before the gains from automation can be felt by those outside the top income percentiles. This leads to a `race between education and technology’ – a race which technology was winning, leading to weaker demand for middle and low-skill workers and rising ‘skill premiums’ for high skilled workers as a result.

Writing in the Financial Times shortly before the financial crisis, Jagdish Bagwati argued that those who looked to globalisation as an explanation for increasing inequality were misguided:

The culprit is not globalization but labour-saving technical change that puts pressure on the wages of the unskilled. Technical change prompts continual economies in the use of unskilled labour. Much empirical argumentation and evidence exists on this. (FT, January 4, 2007, p. 11)

As Krugman put it:

The hypothesis that technological change, by raising the demand for skill, has led to growing inequality is so widespread that at conferences economists often use the abbreviation SBTC – skill-biased technical change – without explanation, assuming that their listeners know what they are talking about (p. 132)

Over the course of his 2007 book, Krugman sets out on a voyage of discovery – ‘That, more or less, is the story I believed when I began working on this book’ (p. 6). He arrives at the astonishing conclusion – ‘[i]t sounds like economic heresy’ (p. 7) – that politics can influence inequality:

[I]nstitutions, norms and the political environment matter a lot more for the distribution of income – and … impersonal market forces matter less – than Economics 101 might lead you to believe (p. 8)

The idea that rising pay at the top of the scale mainly reflect social and political change, … strikes some people as … too much at odds with Economics 101.

If a left-leaning Nobel prize-winning economist has trouble escaping from the confines of Economics 101, what hope for the less sophisticated mind?

As deindustrialisation rolled through the advanced economies, wiping out jobs and communities, economists continued to deny any role for globalisation. As Martin Sandbu argues,

The blithe unconcern displayed by the economics profession and the political elites about whether trade was causing deindustrialisation, social exclusion and rising inequality has begun to seem Pollyannish at best, malicious at worst. Kevin O’Rourke, the Irish economist, and before him Lawrence Summers, former US Treasury Secretary, have called this “the Davos lie.”

For mainstream macroeconomists, inequality was not a subject of any real interest. While the explanation for inequality lay in the microeconomics – the technical forms of production functions – and would be solved by increasing educational attainment, in macroeconomic terms, the use of a representative agent and an aggregate production function simply assumed the problem away. As Stiglitz puts it:

[I]f the distribution of income (say between labor and capital) matters, for example, for aggregate demand and therefore for employment and output, then using an aggregate Cobb-Douglas production function which, with competition, implies that the share of labor is fixed, is not going to be helpful. (p.596)

Robert Lucas summed up his position as follows: ‘Of the tendencies that are harmful to sound economics, the most seductive, and in my opinion the most poisonous, is to focus on questions of distribution.’ It is hard to view this statement as informed more strongly by science than ideology.

But while economists were busy assuming away inequality in their models, incomes continued to diverge in most advanced economies. It was only with the publication of Piketty’s book that the economics profession belatedly began to turn its back on Lucas.

The extent to which economic insecurity in the US and the UK is driven by globalisation versus policy is still under discussion – my answer would be that it is a combination of both – but the skill-biased technical change hypothesis looks to be a dead end – and a costly one at that.

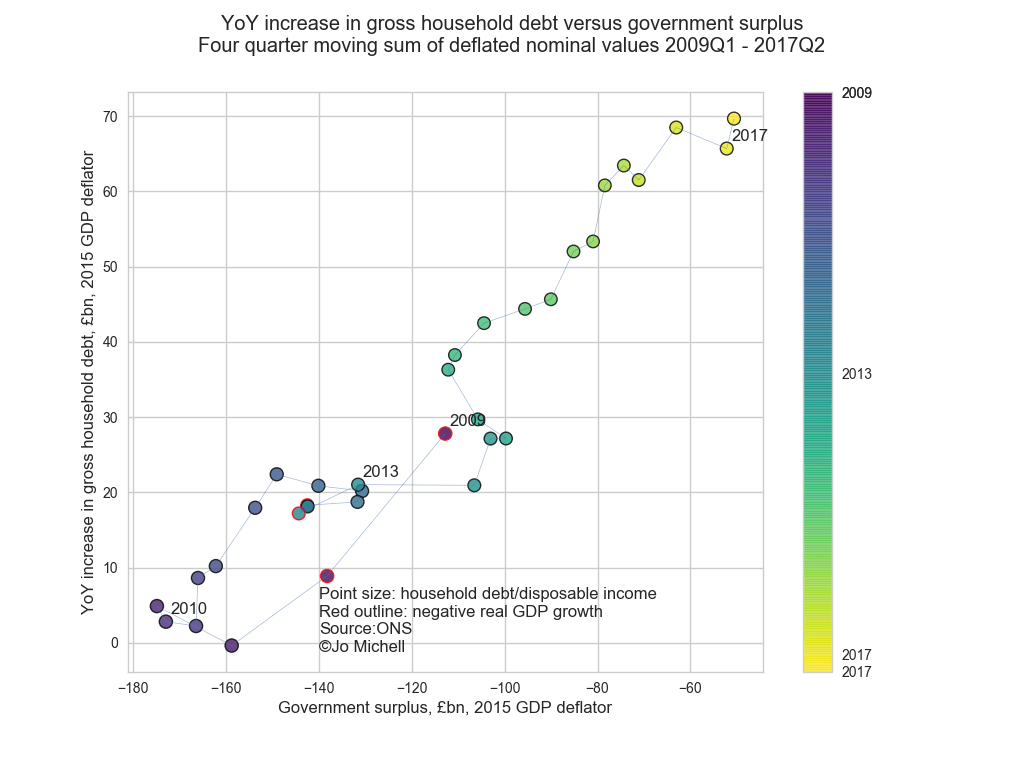

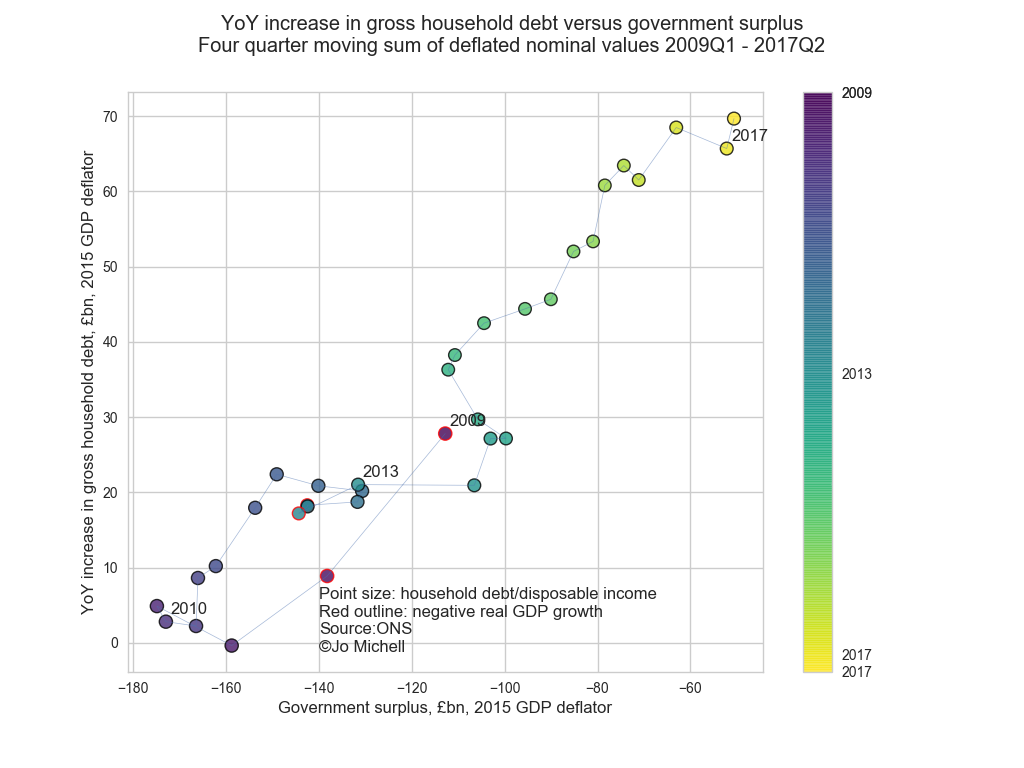

Similar stories can be told about the role of household debt, finance, monetary theory and labour bargaining power and monopoly – why so much academic focus on ‘structural reform’ in the labour market but none on anti-trust policy? Heterodox economists were warning about the connections between finance, globalisation, current account imbalances, inequality, household debt and economic insecurity in the decades before the crisis. These warnings were dismissed as unscientific – in favour of a model which excluded all of these things by design.

Are economic factors – and economic policy – partly to blame for the Brexit and Trump votes? And are academic economists, at least in part, to blame for these polices? The answer to both questions is yes. To argue otherwise is to deny Keynes’ dictum that ‘the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong are more powerful than is commonly understood.’

This quote, ‘mounted and framed, takes pride of place in the entrance hall of the Institute for Economic Affairs’ – the think-tank founded, with Hayek’s encouragement, by Anthony Fisher, as a way to promote and promulgate the ideas of the Mont Pelerin Society. The Institute was a success. Fisher was, in the words of Milton Friedman, ‘the single most important person in the development of Thatcherism’.

The rest, it seems, is history.