Daniela Gabor

On Monday 15th, 2020, I took part in the Public Hearing on COVID19 responses at the European Parliament’s ECON committee. This is the text of my introductory remarks.

The COVID19 pandemic confronted EU members with symmetric shocks and profound deflationary forces. In response, governments are running large budget deficits. Their borrowing costs remain low because central banks have acted as public guarantors of confidence.

I would like to unpack three myths about the COVID19 response in Europe.

Myth 1: central banks have overstepped their mandate with disproportionate interventions in government bond markets, undermining fiscal rules.

This argument, as expressed in the Karlsruhe ruling, implies that it is imperative to return to the pre-crisis status quo: a division of macroeconomic labor whereby the ECB targets price-stability, whereas Member States conduct fiscal and economic policies in a manner consistent with European rules.

Through a macro-financial lens, this argument is simply wrong. If we ask how private financial structure and macroeconomic policies interact*, it becomes clear that evolutionary changes in European finance have joined monetary and fiscal policies at the hip. The pre-crisis division of macroeconomic labor is a fiction that we can no longer afford to sustain.

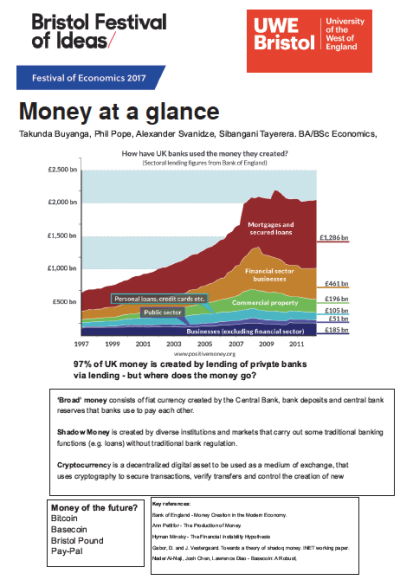

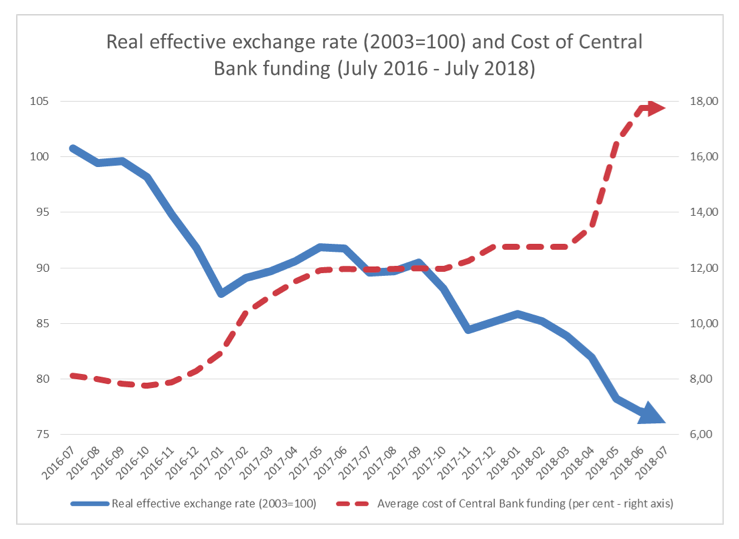

Consider the largest money market for European banks and institutional investors, the €7 trillion repo market. Two out of three euro borrowed through repos use sovereign bonds issued by euro-area members (Germany and Italy the largest) as collateral. Private credit creation —the bread and butter of the ECB’s operations —fundamentally relies on sovereign bonds, and so on fiscal policy. Higher sovereign yields make private credit more expensive. In turn, the repo market creates, and can easily destroy, liquidity for governments, influencing their borrowing conditions and, ultimately, fiscal-policy. In the Euroarea, it creates an exorbitant privilege for Germany: in crisis, banks run to German bunds because these preserve access to collateralised funding. This is why leaders of ‘periphery’ euro countries watch the spread to German bunds nervously.

The ECB did not intervene in sovereign-bond markets because it worried about debt sustainability. As President Lagarde noted in the European Parliament hearing in early June, intervention was needed to effectively support private credit creation, and the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. Improvements in financing conditions for governments, much decried in some European circles, are not a policy target but a side effect of the repo-based sovereign debt order that the founders of the Euro put in place.

But the Euro founders did so without appreciating its complex political ramifications, in particular the structural pressures on central banks to intervene in sovereign bond markets. Given the growing public debt/GDP ratios, and the possibility of renewed pressure on vulnerable sovereigns, it is imperative we rethink this order.

For this, we need to update the institutional framework that governs the relationship between central banks and governments. So far, central banks have improvised through unconventional policy measures, but on terms that they control. In so doing, they entrench a democratic deficit that encourages anti-European sentiment. In the Euroarea, monetary union needs to be accompanied by fiscal union not on grounds of ‘solidarity’, but because the alternative is a disorderly exit from the Euro, particularly if the chorus demanding post-pandemic austerity becomes stronger.

Myth 2 Europe has well-functioning institutions – like the ESM – to provide a safety net for sovereigns in times of crisis.

The Almunia Report on the EFSF/ESM programmes in Greece highlights serious weakness in the institutional mechanisms for backstopping Member States in times of crisis. The ESM put excessive emphasis on fiscal consolidation, with significant social costs for Greek citizens, lacked strategic objectives and prioritized the interests of ESM members over those of Greece. Harsh and counterproductive conditionality for sovereigns stands in clear contrast to the generous support for private finance, as for instance extended by the ECB.

Even if the Almunia recommendations would be enacted in a timely fashion, a reformed ESM can at best alleviate some of the burden of higher public debt. It cannot effectively respond to the cyclical liquidity pressures created by the financial structure described above, particularly as public debt burdens grow across Europe. Equally important, it would not create the fiscal space necessary for Member States to respond counter-cyclically to shocks, and to prioritize green public investments, including public health infrastructure.

This is why the European Commission’s plans for grants under the EU Next Generation are an important first step towards creating an effective European response. But are these enough.

Myth 3 The pandemic recovery plans of the European Commission are ambitious enough.

Bruegel estimates that only a quarter from the grants envisaged in the Next Generation EU will be spent over 2020-2022**. National fiscal policies will have to shoulder the burden of recovery. The EU can and should be more ambitious, prioritizing a green recovery.

It is encouraging that the Commission has reaffirmed its intentions to reserve 25% of EU spending for climate-friendly expenditure. Its efforts should be amplified by pre-crisis commitments to green central banks and to promote sustainable finance in Europe.

Take the ECB. Its support to market actors comes without environmental, tax- or payout-related conditionality. In practice, the ECB continues to subsidise high-carbon activities, and in doing so, it reinforces climate-related risks to financial stability. Its objectives can be recalibrated within the existing treaty framework, as follows***:

- The ECB should start to love ‘brown inflation’. In its current version, the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices ignores the carbon footprint of goods and services. Greening the HICP would take the bite out of the price-stability mandate, while rendering it more consistent with the ECB’s secondary objective.

- The ECB should green its monetary policy operations, by removing the preferential treatment to brown assets, and where it judges necessary, by promoting green financial instruments. These two measures should go hand in hand to avoid greenwashing, and would constitute an effective measure to reorient private finance towards sustainable activities.

- The Euroarea should institute an open and recurrent process at the highest political level to specify which ‘general economic policies in the Union’ the ECB is required to support. Article 11 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union already mandates ‘environmental protection’. Specifying such protection in relation to the full portfolio of central-bank activities—considerably broader than monetary policy proper—would provide political legitimacy for an unconditional ECB backstop of green public investment. This circular arrangement would amount to a substantial gain in fiscal sovereignty in the euro area.

In parallel, the European Commission, with support from the European Parliament, should accelerate its work on the Renewed Sustainable Finance strategy. A well-defined taxonomy for green and brown activities, and prudential measures guided by the taxonomy, would ensure that private financing of brown activities does not undermine the public investments in the green recovery.

Thank you for your time.

——–

* See Gabor, D. (2020) Critical macro-finance: a theoretical lens. Finance and Society 6(1): 45-55.

**See Darvas, Z. (2020) Three-quarters of Next Generation EU payments will have to wait until 2023. https://www.bruegel.org/2020/06/three-quarters-of-next-generation-eu-payments-will-have-to-wait-until-2023/

*** See Braun, B., Gabor, D. and B. Lemoine (2020) Enlarging the ECB mandate for the common good and the planet. Social Europe. https://www.socialeurope.eu/enlarging-the-ecb-mandate-for-the-common-good-and-the-planet

At first sight, this is a compelling argument, in Mehrling’s

At first sight, this is a compelling argument, in Mehrling’s