MMT continues to generate debate. Recent contributions include Jonathan Portes’ critique in Prospect and Stephanie Kelton’s Bloomberg op-ed downplaying the AOC and Warren tax proposals.

Something that caught my eye in Jonathans’ discussion was this quote from Richard Murphy: “A government with a balanced budget necessarily denies an economy the funds it needs to function.” This is an odd claim, and not something that follows from MMT.

Richard has responded to Jonathan’s article, predictably enough with straw man accusations, and declaring, somewhat grandiosely, that “the left and Labour really do need to adopt the core ideas of modern monetary theory … This debate is now at the heart of what it is to be on the left”

Richard included a six-point definition of what he regards to be the core propositions of MMT. Paraphrasing in some cases, these are:

- All money is created by the state or other banks acting under state licence

- Money only has value because the government promises to back it …

- … because taxes must be paid in government-issued money

- Therefore government spending comes before taxation

- Government deficits are necessary and good because without them the means to make settlement would not exist in our economy

- This liberates us to think entirely afresh about fiscal policy

Of these, I’d say the first is true, with some caveats, the second and third are partially true, and the fourth is sort of true but also not particularly interesting. I’ll leave further elaboration for another time, because I want to focus on point five, which is almost a restatement of the quote in Jonathan’s Prospect piece.

This claim is neither correct nor part of MMT. I don’t believe that any of the core MMT scholars would argue that deficits are required to ensure that there is sufficient money in circulation. (Since Richard uses the term “funds” in the first quote and “means [of] settlement” in the second, I’m going to assume he means money).

To see why, consider what makes up “money” in a modern monetary system. Bank deposits are the bulk of the money we use. These are issued by private banks when they make loans. Bank notes, issued by the Bank of England make up a much smaller proportion of the money in the hands of the public. Finally, there are the balances that private banks hold at the Bank of England, called reserves.

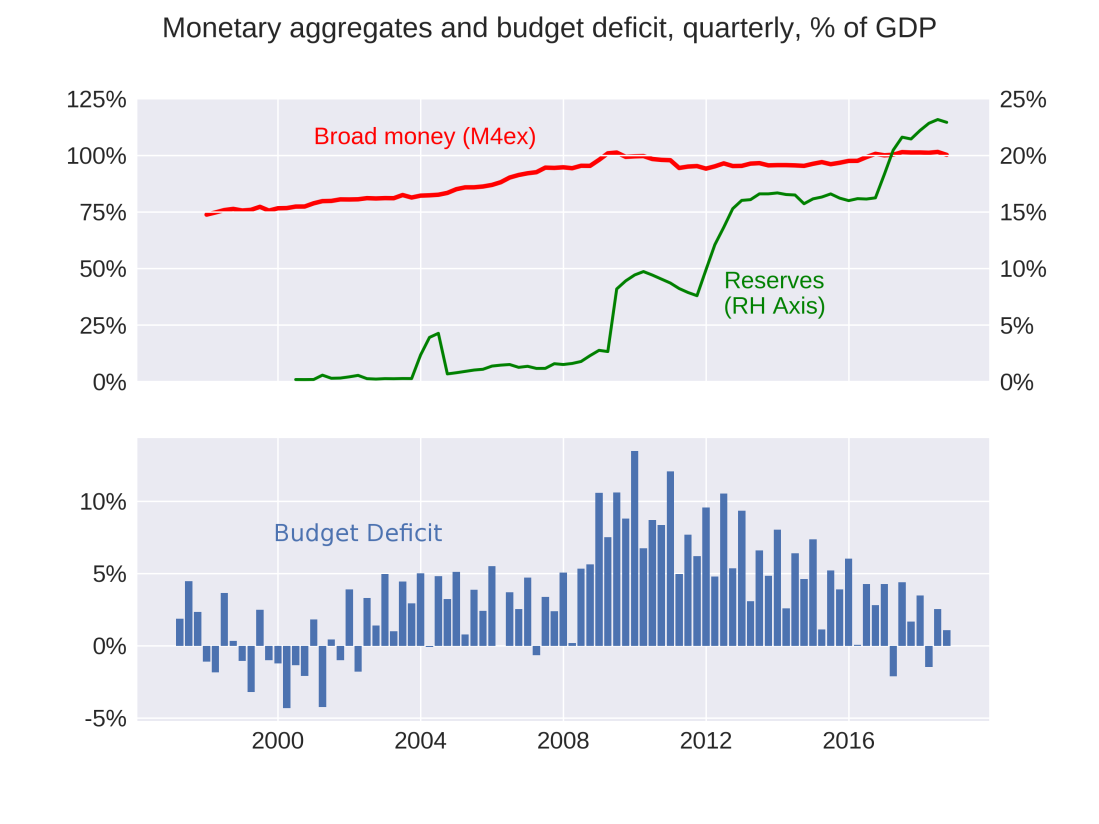

What is the relationship between these types of money and the government surplus or deficit? The figure below shows how both deposits and reserves have changed over time, alongside the deficit.

Can you spot a connection between the deficit and either of the two money measures? No, that’s because there isn’t one — and there is no reason to expect one.

Reserves increase when the Bank of England lends to commercial banks or purchases assets from the private sector. Deposits increase when commercial banks lend to households or firms. Until 2008, the Bank of England’s inflation targeting framework meant it aimed to keep the amount of reserves in the system low — it ran a tight balance sheet. Following the crisis, QE was introduced and the Bank rapidly increased reserves by purchasing government debt from private financial institutions. Over this period, and despite the increase in reserves, the ratio of deposits to GDP remained pretty stable.

The quantity of neither reserves nor deposits have any direct relationship with the government deficit. This is because the deficit is financed using bonds. For every £1bn of reserves and deposits created when the government spends in excess of taxation, £1bn of reserves and deposits are withdrawn when the Treasury sells bonds to finance that deficit.

This is exactly what MMT says will happen (although MMT also argues that these bond sales may not always be necessary). So MMT nowhere makes the claim that deficits are required to ensure that the system has enough money to function.

It is true that the smooth operation of the banking and financial system relies on well-functioning markets in government bonds. During the Clinton Presidency there were concerns that budget surpluses might lead the government to pay back all debt, thus leaving the financial system high and dry.

But the UK is not in any danger of running out of government debt. Government surpluses or deficits thus have no bearing on the ability of the monetary system to function.

The macroeconomic reason for running a deficit is straightforward and has nothing to do with money. The government should run a deficit when the desired saving of the private sector exceeds the sum of private investment expenditure and the surplus with the rest of the world. This is not an insight of MMT: it was stated by Kalecki and Keynes in the 1930s.

If a debate about MMT really is at “the heart of what it is to be on the left” then Richard might want to take a break to get up to speed on MMT (and monetary economics) before that debate continues.

I agree. But it might be useful to point out the monetary options MMT suggests for utilizing unproductive assets in the material productive economy. More specifically, what institutional entities have agency to enable productive resources? The left’s slant on such activity is to create economic activity outside of firm centered return to capital considerations.

LikeLike

Quality stuff there from Jo Michell. My only quibble is that there is no sharp distinction between base money and government debt as Martin Wolf and others have pointed out. E.g. £X of government debt which pays almost no interest and matures in a week’s time is virtually the same thing as £X of base money, which pays no interest at all (e.g. a wad of £10 notes).

So the statement that “deficits are required to ensure that the system has enough money to function” is arguably true if one is using the word “money” in a very vague or broad sense: i.e. to include all forms of very liquid assets, like government debt with less than a month to maturity, for example.

But to repeat, that’s a minor quibble, not an attempt to contradict Jo Michell.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Sorry Jo you don’t understand money. As Kalecki whom you mention said ‘ Money is what we need to buy stuff ‘ . And it doesn’t matter who that whom is . So government created money ( when it spends ) makes up a large percentage of money in circulation. Your trope ‘ bank loans create money ‘ variously computed at around 97% is simply bollocks. I’ve made film about money creation ( Money for Nothing ) which has been on YouTube for three months with 5000 plus views . It tells exactly and precisely how money is created and by whom.

LikeLike

Great critique!

LikeLike

If you want anyone to look at your film, it would have been an idea to give a link to it. I tried Googling, but found nothing. That all rather calls into question your competence.

LikeLike

In order to purchase reserves from the central bank the clearing banks (commercial banks) need the money to do so. From a macro-accounting perspective this money can only come from government deficit spending. For the clearing banks to be able to create their own “government” reserves would result in control fraud!

LikeLike

No, commercial banks borrow reserves from the central bank, often using government debt as collateral to do so.

LikeLike

You need to do the macro-accounting but let’s do it your fully complex way. Where do they get the money in macro-accounting terms from to buy government debt to set up as a bank in the first place? Second where do they get the money from again in macro-accounting terms to buy government debt to use as collateral to “buy” government debt to expand their loan book? I am of course assuming in my questions you do understand one function of government reserves is to facilitate the payments settlement system the other to control the base interest rate and that the government central bank can create reserves without a corresponding balance sheet liability. In other words it doesn’t have to borrow the money from anybody else to create the reserves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

From MMT misunderstandings to the true Theory of Money

Comment on Jo Michell on ‘Misunderstanding MMT’#1, #2

Jo Michell summarizes what Robert Murphy says are his core points of MMT:

1. All money is created by the state or other banks acting under state licence

2. Money only has value because the government promises to back it …

3. … because taxes must be paid in government-issued money

4. Therefore government spending comes before taxation

5. Government deficits are necessary and good because without them the means to make settlement would not exist in our economy

6. This liberates us to think entirely afresh about fiscal policy

Jo Michell focuses his critique on point 5 and concludes: “The macroeconomic reason for running a deficit is straightforward and has nothing to do with money. The government should run a deficit when the desired saving of the private sector exceeds the sum of private investment expenditure and the surplus with the rest of the world. This is not an insight of MMT: it was stated by Kalecki and Keynes in the 1930s.”

Because already point 2. of Robert Murphy’s list can be shown to be false, there is no need to say anything about Jo Michell’s argument.

In order to see where MMT fails, one has to start with the most elementary version of what Keynes called the “monetary theory of production”.

As the analytical starting point, the elementary production-consumption economy is defined with this set of macroeconomic axioms: (A0) The economy consists of the household and the business sector which, in turn, consists initially of one giant fully integrated firm. (A1) Yw=WL wage income Yw is equal to wage rate W times working hours. L, (A2) O=RL output O is equal to productivity R times working hours L, (A3) C=PX consumption expenditure C is equal to price P times quantity bought/sold X.

Under the conditions of market clearing X=O and budget balancing C=Yw in each period, the price is given by P=W/R (1). The price P is determined by the wage rate W, which takes the role of the nominal numéraire, and the productivity R. This translates into W/P=R (2), i.e. the real wage is equal to the productivity.

Monetary profit/loss of the business sector is defined as Qm≡C−Yw and monetary saving/dissaving of the household sector is defined as Sm≡Yw−C. It always holds Qm+Sm=0, or Qm=−Sm, in other words, the business sector’s nominal surplus = profit equals the household sector’s nominal deficit = dissaving. Vice versa, the business sector’s deficit = loss equals the household sector’s surplus = saving. Under the initial condition of budget balancing C=Yw, total monetary profit is zero.

What is needed for a start is two things (i) a central bank which creates money on its balance sheet in the form of deposits, and (ii), a legal system which declares the central bank’s deposits as legal tender.

Deposit money is needed by the business sector to pay the workers who receive the wage income Yw per period. The need is only temporary because the business sector gets the money back if the workers fully spend their income, i.e. if C=Yw. Overdrafts are needed by the household sector for consumption expenditures if the households want to spend before they get their income.

For the case of a balanced budget C=Yw, the idealized transaction pattern of deposits/overdrafts of the household sector at the central bank over the course of one period is shown on Wikimedia.#3

The household sector’s deposits/overdrafts are zero at the beginning and end of the period. Money is continually created and destroyed during the period under consideration. There is NO such thing as a fixed quantity of money. The central bank plays an accommodative role and simply supports the autonomous market transactions between the household and the business sector.

See part 2

LikeLike

Part 2

From this follows the average stock of transaction money as M=kYw, with k determined by the transaction pattern. In other words, the average stock of money M is determined by the autonomous transactions of the household and business sector and created out of nothing by the central bank.

The transaction equation reads M=kWL in the case of budget balancing and market clearing. If employment L is doubled, the average stock of transaction money M doubles. In a well-designed fiat money economy, growth is not hampered by a lack of the transaction medium.

So, the crucial point is to make sure that the business sector gets transaction money from the central bank if it plans to increase employment. In the old days, firms issued bills of exchange which were discounted by the banking system and redeemed within a short time span. Something a bit more sophisticated is required to ensure that the business sector is in no way hampered by a lack of transaction money. That is a question of the institutional design of the central bank.

In sum, (i) money is a generalized IOU (ii) no taxes are needed to get the monetary economy going and growing, (iii) there is NO fixed quantity of money, (iv) money is created and destroyed by the transactions between the household and the business sector, (v) money is endogenous, (vi) the value of money is given by W/P=R, i.e. is equal to the productivity, (vii) if the rate of change of the wage rate W is equal to the rate of change of productivity R there is neither inflation nor deflation.

The unhindered creation of fiat money for the payment of the wage bill is the correct way of bringing money into the economy. MMT’s deficit-spending is the incorrect way. Why? Because of the macroeconomic Profit Law, it holds Public Deficit = Private Profit, in other words, bringing money at the demand side into the economy creates a free lunch for the Oligarchy.#4

When all misunderstandings are clarified, this is the ultimate reason why self-styled Progressives like Richard Murphy want Labour so badly to adopt MMT’s policy of deficit-spending/money-creation.#5, #6

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

#1 Jo Michell, Misunderstanding MMT

#2 Richard Murphy, Why the left and Labour really do need to adopt the core ideas of modern monetary theory

https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2019/02/02/why-the-left-and-labour-really-do-need-to-adopt-the-core-ideas-of-modern-monetary-theory/

#3 Wikimedia, Idealized transaction pattern

#4 Keynes, Lerner, MMT, Trump and exploding profit

https://axecorg.blogspot.com/2017/12/keynes-lerner-mmt-trump-and-exploding.html

#5 Very busy these days: Wall Street’s agents

https://axecorg.blogspot.com/2018/10/very-busy-these-days-wall-streets-agents.html

#6 Why the British Labour Party should NOT adopt MMT

https://axecorg.blogspot.com/2018/08/why-british-labor-party-should-not.html

LikeLike

You’re right. What depresses me is that this needs saying at all. I remember the debates in the 80s about over- or underfunding the PSBR (as it was then) which established that there was no necessary link between govt borrowing and money creation because as you say bond issues reduce the money stock. I also remember reading the BoE’s “counterparts to M4” press releases every month as part of my job (they still issue something like it) which showed clearly that it was banks that created most of the M4 stock (until the 08 crisis!). It saddens me that people still need to learn what we all knew back in the 80s.

LikeLike

Murphy’s statement is mostly true *in practice.* Assuming a balanced current account, then keeping the financial assets of the private sector fixed will place deflationary pressure on an economy over time. Private credit can provide an assist, but it is unsustainable, because there is only so much debt the private sector can carry. The financial assets available to the private sector has to grow with growth in output (this is price stability 101) as well as with a growing population size. Thus, on average, and assuming a closed economy, deficits will have to be run annually.

Now throw in an external sector. A country with a current account surplus (Norway, Germany) has an inflow of financial assets from abroad. Depending on the size of the surplus, this nation’s government may not need to run deficits to sustain growth and stave off deflation. But a country with a current account deficit (US, UK) has no choice but to run even higher deficits than would be necessary in a closed economy, because in addition to staving off deflation and growing the economy, it has to replace the *outflow* of financial assets from the current account deficit.

All of this flows from sectoral balance analysis, i.e., accounting identities. It cannot be reasonably disputed, and it cannot be avoided. Luckily, what MMT shows us is that monetarily sovereign countries have no problem supplying their private sectors with however much financial assets are needed to make use of all available resources within it.

LikeLike

But this isn’t what I’m arguing against. Murphy’s argument was about the money supply. I say effectively the same as you at the end of the blog.

LikeLike

I don’t disagree, but I was specifically defending the original comment from Murphy you quoted and were taking issue with, which was that “[a] government with a balanced budget necessarily denies an economy the funds it needs to function.” This is true for a closed economy, which Murphy may have had in mind for simplification when he wrote it. And while not technically accurate as written for an open economy (because of the “necessarily”), the thrust of it is nevertheless true, and I think is generally a fair comment. Especially as Murphy is in the UK and writes primarily for a UK audience. The UK has a large current account deficit, so he may even be contemplating an open economy with a current account deficit.

While Murphy did make the statement you make, the statement that appears in the Portes piece was different. It was: “Experience in recent years has suggested that total tax revenues should be less than total government spending or additional money supplies required to ensure the liquidity to permit growth is not present in the economy.” This is (1) directed at the UK economy and (2) not as broad as the statement in your piece. All this to say, I’m not sure there’s much to criticize here.

(And, just for the record, Murphy is not an MMTer. He considers himself “sympathetic,” but (from the post you linked to) has “for some time been quite critical of some of its leading exponents.” So all of the writing about what he says is not really discussing MMT or any of the literature produced by its developers.)

LikeLike

Yes, Murphy is being imprecise. Here is the MMT orthodox view of money creation, covering bank lending, taxes and deficits. https://elliswinningham.net/index.php/2019/02/05/on-national-government-spending-taxation-and-bank-lending-in-the-united-kingdom/

Which is why when they do sectoral balances it sums to zero.

LikeLike

Under current institutional arrangements, the fiscal arm of government (the Treasury) is not permitted to overdraw at its account held at the central bank (the monetary arm). For this reason, the government must issue bonds BEFORE it deficit spends into the real economy.

Further, tax receipts are not destroyed by the government on receipt. Instead, there is a transfer at the central bank from bank deposits to government deposits. To suggest otherwise is to jettison double-entry principles, which is odd since MMT prides itself on its accountant’s approach to economics.

Modelling bond issues as happening before deficit spending takes place does not alter Jo’s point, which if I understand it correctly, is that deficit spending does not, per se, increase the money supply. An exception may arise when purchases of fresh issues of bonds are funded by the lenders borrowing from the commercial banks. Under those circumstances new money is injected into circulation.

LikeLike

Possibly a minor point, but could be important when modelling the process of deficit financing:

Under current institutional arrangements the fiscal arm of government ( the Treasury) is not permitted to overdraw at its account held at the central bank (the monetary arm). Hence the idea that the government spends first and then borrows to pay off its overdraft is erroneous in my humble view.

For modelling purposes, it makes more sense to have the government issue bonds first and then spend the proceeds into the real economy after its account at the Bank of England has been re-stocked with the issue proceeds.

Either way, the results are that deficit spending does not cause a rise in the money supply, which I believe is the point that Jo is making.

NB. There could be a rise in the money supply if investors need to borrow from the commercial banks to fund their purchases of a fresh issue of bonds.

LikeLike

“Under current institutional arrangements, the fiscal arm of government (the Treasury) is not permitted to overdraw at its account held at the central bank (the monetary arm).”

Are you sure about that? Can you cite a legal provision? (This is a serious question, as I’m not sure there is one and I would love for somebody to tell me where that provision is if it exists.)

“For this reason, the government must issue bonds BEFORE it deficit spends into the real economy.”

That’s true, at least as to practice (and possibly law although I have my doubts), but even if it is, it doesn’t change the *nature* of the operations, because the government is indisputably the currency issuer. In other words, it can always be conceived of issuing its currency ex nihilo when it spends. Bond sales are just an additional spending operation that occurs *on top of* that. Even if legally required, they dictate a *procedure*, but do not transform the character of currency creation at the moment of spending.

“Further, tax receipts are not destroyed by the government on receipt. Instead, there is a transfer at the central bank from bank deposits to government deposits. To suggest otherwise is to jettison double-entry principles, which is odd since MMT prides itself on its accountant’s approach to economics.”

MMT would not dispute this. Indeed, it is hyperfocused on the actual operations within the banking sector and federal reserve. What MMT would dispute is that the “government deposits” entry has any meaningful significance. Currency in the possession of a currency-issuer becomes nothing (which is why we can say it is “destroyed”). One can, if one wants, “account” for it, which is what we do in practice, but since the government always has an infinite supply of its unit of account (like a scoreboard operator has an infinite supply of points to award at a sporting match), it becomes meaningless, or the mathematical equivalent of destruction (what’s 1 + infinity?).

LikeLiked by 1 person

@pigswiggle

Thanks for replying.

To answer your question, I am providing a link below to an IMF article which reports on the very question you ask, i.e. “where is the legal authority that prohibits central bank funding of fiscal deficits?”

This IMF research reports on the institutional arrangements of a sample of countries and so is not a census, but included in the sample are 6 EU countries: France Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden. The UK is not included in the sample. The central banks of all six of the EU countries are forbidden by Article 101 of the Treaty Establishing the EC of 20 December 2006 from funding fiscal deficits. This Treaty appears to be the legal authority that forbids central bank deficit funding in the EU.

There is no reason to suppose that the UK is exempt from A101 on the ground that it doesn’t use the Euro because Sweden does not use the Euro but is nonetheless caught by A101. Hence I assume the UK is barred from central bank deficit funding by A101 of the Treaty, just as Sweden is, although I may be wrong to assume this.

The IMF research also, I believe, reports that the USA Federal Reserve is also severely restricted by US law from funding fiscal deficits (only very short dated bonds and bills can be so used).

The research reports that restrictions and prohibitions on central bank deficit funding are more prevalent in developed countries. This seems to refute MMT’s assertion that its school of thought merely describes the operation of financial systems in developed countries. The US financial system can not operate in the way MMT says if the Fed’s ability to fund the US deficit is so severely limited by law.

Click to access wp1216.pdf

LikeLike

Under current institutional arrangements, the fiscal arm of government (the Treasury) is not permitted to overdraw at its account held at the central bank (the monetary arm). For this reason, the government must issue bonds BEFORE it deficit spends into the real economy.

Further, tax receipts are not destroyed by the government on receipt. Instead, there is a transfer at the central bank from bank deposits to government deposits. To suggest otherwise is to jettison double-entry principles, which is odd since MMT prides itself on its accountant’s approach to economics.

Modelling bond issues as happening before deficit spending takes place does not alter Jo’s point, which if I understand it correctly, is that deficit spending does not, per se, increase the money supply. An exception may arise when purchases of fresh issues of bonds are funded by the lenders borrowing from the commercial banks. Under those circumstances new money is injected into circulation.

LikeLike

The reason deficit funding of domestic programs is required is because taxation causes involuntary unemployment. Every dollar taxed is a dollar that can’t be paid or earned.

Warren Mosler says it’s highly likely that our economy needs far less taxation at the federal level, and far more deficit funded domestic programs, such as employment guarantee programs, universal healthcare, education, roads and bridges, whatever we decide our society wants to pay for.

Deficit funding anything will cause the public debt to rise. But that isn’t very important. Japan routinely runs deficits at 250% of their GDP. What is important is what the money is spent on.

If $7.8 Trillion is spent on two unnecessary wars in the Middle East, that’s wasted money. You might as well light that money on fire in the middle of the desert. Yes, some soldiers got paid to kill brown people in foreign nations. But that did not positively affect our economy. We would have been better off paying those soldiers to clean up dry underbrush in California. Think about it.

“National Defense”?

If we instead spend several Trillion $ on a deficit funded Federal Employment Guarantee program, that money immediately begins to be paid to project managers, administrators, then construction contractors, skilled laborers, unskilled laborers, then staff that will work at the regional federal employment offices, janitors who work in the facilities, and then people will be hired based on each region’s need for a particular service or good which the proposed worker has the skill, knowledge, and willingness to provide or create.

That money begins being spent into the economy the same day that the first people hired receive their first paychecks. People will be buying their food, paying their rent, electric bills, car payments, their kid’s school equipment, going out to dinner.

Everything that makes America great. If the government can spend more money on military action than nearly every country on earth combined, we can afford to literally purchase a utopian society on the backs of every working man and woman in the nation. Make our labor worth something. Don’t let corporate executives continue stealing 80% or more of our productivity. There is a better way, and our currency is sufficiently powerful, resilient, and plentiful to achieve a society we can all be proud of.

MMT describes the processes that create the policy space to do it.

LikeLike

Paragraph 1 of Article 101 of the Treaty of the EU says this about deficits:

1. Overdraft facilities or any other type of credit facility with the ECB or with the central banks of the Member States (hereinafter referred to as ‘national central banks’) in favour of Community institutions or bodies, central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of Member States shall be prohibited, as shall the purchase directly from them by the ECB or national central banks of debt instruments.

LikeLike

I wonder if this might help add to the debate about what happens to tax receipts in the UK. The money goes to HMRC and then to the Bank of England. Although, a figuratively small amount, however is sent by HMRC directly to the Health and Education departments without being sent to the BoE. See the FOI request here: https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/what_happens_to_the_tax_revenue#incoming-1148445

LikeLike

Bank deposits do not make up the bulk of loans.

LikeLike