Towards the end of last year, the Guardian published an opinion piece arguing there is a link between climate change and the monetary system. The author, Jason Hickel, claims our current monetary system induces a need for continuous economic growth – and is therefore an important cause of global warming. As a solution, Hickel endorses the full reserve banking proposals put forward by the pressure group Positive Money (PM).

This is an argument I encounter regularly. It appears to have become the default position among many environmental activists: it is official Green Party policy. This is unfortunate because both the diagnosis of the problem and the proposed remedy are mistaken. It is one element of a broader set of arguments about money and banking put forward by PM. (Hickel is not part of PM, but his article was promoted by PM on social media, and similar arguments can be found on the PM website.)

The PM analysis starts from the observation that money in modern economies is mostly issued by private banks: most of what we think of as money is not physical cash but customer deposits at retail banks. Further, for a bank to make a loan, it does not require someone to first make a cash deposit. Instead, when a bank makes a loan it creates money ‘out of thin air’. Bank lending increases the amount of money in the system.

This is true. And, as Positive Money rightly note, neither the mechanism nor the implications are widely understood. But Positive Money do little to increase public understanding – instead of explaining the issues clearly, they imbue this money creation process with an unnecessary air of mysticism.

This isn’t difficult. As J. K. Galbraith famously observed: ‘The process by which banks create money is so simple the mind is repelled. With something so important, a deeper mystery seems only decent.’

To the average person, money appears as something solid, tangible, concrete. For most, money – or lack of it – is an important (if not overwhelming) constraint on their lives. How can money be something which is just created out of thin air? What awful joke is this?

This leads to what Perry Mehrling calls the ‘fetish of the real’ and ‘alchemy resistance’ – people instinctively feel they have been duped and look for a route back to solid ground. Positive Money exploit this unease but deepen the confusion by providing an inaccurate account of the functioning of the monetary and financial system.

There is nothing new about the ‘fetish of the real’. Economists have been trying to separate the ‘real’ economy from the financial system for centuries. Restrictive ‘tight money’ proposals have more commonly been associated with free-market economists on the political right, while economists inclined towards collectivism have favoured less monetary restriction. One reason is that the right tends to view inflation as the key macroeconomic danger while the left is more concerned with unemployment.

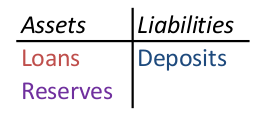

The original blueprint for the Positive Money proposal is known as the Chicago Plan, named after a group of University of Chicago economists who argued for the replacement of ‘fractional reserve’ banking with ‘full reserve banking’. To understand what this means, look at the balance sheet below.

The table shows a stylised list of the assets and liabilities on a bank balance sheet. On the asset side, banks hold loans made to customers and ‘reserve balances’ (or ‘reserves’ for short). The latter item is a claim on the Central Bank – for example, the Bank of England in the UK. These reserve balances are used when banks make payments among themselves. Reserves can also be swapped on demand for physical cash at the Central Bank. Since only the Central Bank can create and issue these reserves, alongside physical cash, they form the part of the ‘money supply’ which is under direct state control.

For banks, reserves therefore play a role similar to that of deposits for the general public – they allow them to obtain cash on demand or to make payments directly between their individual accounts at the Bank of England

The only thing on the liability side is customer deposits – what we think of as ‘money’. These deposits can increase for two reasons. If customers decide to ‘deposit’ cash with the bank, the bank accepts the cash (which it will probably swap for reserves at the Central Bank) and adds a deposit balance for that customer. Both sides of the bank balance sheet increase by the same amount: a deposit of £100 cash will lead to an increase in reserves of £100 and an increase in deposits of £100.

Most increases in deposits happen a different way, however. When a bank makes a loan, both sides of its balance sheet increase as in the above example – except this time ‘loans’ not ‘reserves’ increases on the asset side. When a bank lends £100 to a customer, both ‘loans’ and ‘deposits’ increase by £100. Absent any other changes, the amount of money in the world increases by £100: money has been created ’out of nothing’.

The Positive Money proposal – like the Chicago Plan of the 1930s – would outlaw this money-creating power. Under the proposal, banks would not be allowed to make loans: the only asset allowed on their balance sheet would be ‘reserves’ – hence the name ‘full reserve banking’. Since reserves can only be issued by the Central Bank, private banks would lose their ability to create new money when they make loans.

What’s wrong with the PM proposal? To answer, we first need to ask what problem PM are trying to solve. They list several issues on their website: environmental degradation, inequality, financial instability and a lack of decent jobs. How does Positive Money think the monetary system contributes to these problems? The following quote and diagram, taken from the Positive Money website, give the crux of the argument:

The ‘real’ (non-financial), productive economy needs money to function, but because all money is created as debt, that sector also has to pay interest to the banks in order to function. This means that the real-economy businesses – shops, offices, factories etc – end up subsidising the banking sector. The more private debt in the economy, the more money is sucked out of the real economy and into the financial sector.

This illustrates the central misconception in PM’s description of money and banking. The ‘real economy’ needs money to operate – so individuals and business can make payments. This is correct. But PM imply that in order to obtain this money, the ‘real economy’ must borrow from the banks. And because the banks charge interest on this lending, they then end up sucking money back out of the ‘real economy’ as interest payments. In order to cover these payments, the ‘real economy’ must obtain more money – which it has to borrow at interest! And so on.

If this were a genuine description of the monetary system, the debts of the ‘real economy’ to the banks would grow uncontrollably and the system would have collapsed decades ago – PM essentially describes a pyramid scheme. The connection to the ‘infinite growth’ narrative is also clear – the ‘real economy’ is forced to produce ever more output just to feed the banks, destroying the environment in the process.

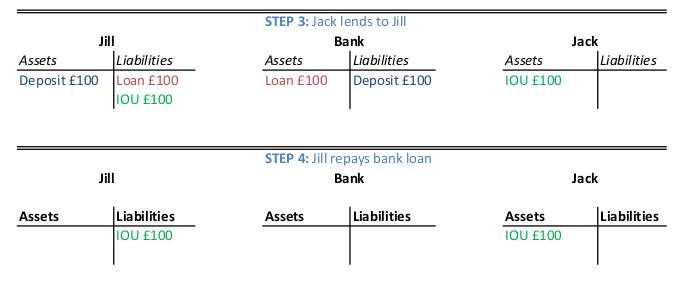

But neither the quote nor the diagram is accurate. To illustrate, look at the diagram below. It shows a bank, with a balance sheet as above, along with two individuals, Jack and Jill. Two steps are shown. In the first step, Jill takes out a loan from the bank – the bank creates new money as it lends. In the second step, Jill uses this money to buy something from Jack. Jack ends up holding a deposit while Jill is left with a loan to the bank outstanding. The bank sits between the two individuals.

The point here is twofold. First, the ultimate creditor – the person providing credit to Jill – is not the bank, but Jack. Jack has lent to Jill, with the bank acting as a ‘middleman’. The bank is not a net lender, but an intermediary between Jill and Jack – albeit one with a very important function: it guarantees Jill’s loan. If Jill doesn’t make good on her promise to pay, the bank will take the hit – not Jack. Second, the initial decision to lend wasn’t made by Jack – it was made by the bank. By inserting itself between Jack and Jill, and substituting Jill’s guarantee with its own, the bank allows Jill to borrow and spend without Jack first choosing to lend. But in accepting a deposit as a payment, Jack also makes a loan – to the bank. As well as acting as ‘money’, a bank deposit is a credit relationship: a loan from the deposit-holder to the bank.

A more accurate depiction of the outcome of bank lending is therefore the following:

Jill will be charged interest on her loan – but Jack will also receive interest on his deposit. Interest payments don’t flow in only one direction – to the bank – as in the PM diagram. Instead interest flows both in and out of the bank, which makes its profits on the ‘spread’, (the difference) between the two interest rates: it will charge Jill a higher rate than it pays Jack. This is not to argue that there aren’t deep problems with the ways the banking system is able to generate large profits, often through unproductive or even fraudulent activity – but rather that money creation by banks does not cause the problems suggested by Positive Money.

So the banks don’t endlessly siphon off income from the ‘real economy’ – but isn’t it still the case that in order to obtain money for payments, someone has to borrow at interest and someone else has to lend?

To see why this is misleading, we need to consider not only how money is created but also how it is destroyed. We’ve already seen how new money is created when a bank makes a loan. The process also happens in reverse: money is destroyed when loans are repaid. For example, if after the steps above, Jack were to subsequently buy something from Jill, the deposit will return to her ownership and she can pay off her loan – extinguishing money in the process.

One possibility is that instead of selling goods to Jack – for example a phone or a bike – Jill ‘sells’ Jack an IOU: a private loan agreement between the two of them. In this case Jill can pay off her loan to the bank and replace it with a direct loan from Jack. This would leave the balance sheets looking as follows:

Note that after Jill repays her loan, the bank is no longer involved – there is only a direct credit relationship between Jack and Jill.

This mechanism operates constantly in the modern economy – individuals swap bank deposits for other financial assets, or pay a proportion of their wages into a pension scheme. In fact, the volume of non-bank financial intermediation outweighs the volume of bank lending. The implication is that the demand from individuals for interest-bearing financial instruments is greater than the demand for bank deposits as a means of payment. Rather than banks being able to force loans on people because of their need for money to make payments, the opposite is true: people save for their future by getting rid of money and swapping it for other financial assets.

The quantity of money in the system isn’t determined by bank lending, as in the PM account. Instead it is a residual – the amount of deposits remaining in customer accounts after firms borrow, hire and invest; workers receive wages, consume and save; and the financial systems matches savers to borrower directly through equity and bond markets, pension funds and other non-bank mechanisms.

So the monetary argument is wrong. What of the argument that lending at interest requires endless economic growth?

Economic growth can be broken down into two components: population increase and growth in output per person. For around the last 100 years, global GDP growth of around 3 per cent per year has been split evenly between these two factors: about 1.5 per cent was due to population growth. The economy is growing because there are more people in it. This is not caused by bank lending. Further, projections suggest that the global population will peak by around 2050 then begin to fall as a result of falling fertility rates.

What about growth of output per head? Again, the answer is no. There is simply no mechanistic link between lending at interest and economic growth. Interest flows distribute income from one group of people to another – from borrowers to lenders. Government taxation and social security payments play a similar role. Among other functions, lending and borrowing at interest provides a mechanism by which people can accumulate financial claims during their working life which allow them to receive an income after retirement when they consume out of previously acquired wealth. This mechanism is perfectly compatible with zero or negative growth.

If anything, excessive lending is likely to cause lower growth in the long run: in the aftermath of big credit expansions and busts, economic growth declines as households and firms reduce spending in an attempt to pay down debt.

Even if we did want to reduce growth rates, history teaches us that using monetary means to do so is a very bad idea. During the monetarist experiment of the early 1980s, the Thatcher government tried exactly this: they restricted growth of the money supply, ostensibly in an attempt to reduce inflation. The result was a recession in which 3 million people were out of work.

Oddly, despite the environmental argument, we can also find arguments from PM about ways that monetary mechanisms can be used to induce higher output and employment. These proposals, which go by titles such as ‘Green QE’ and ‘People’s QE’, argue that the government should issue new money and use it to pay for infrastructure spending.

An increase in government infrastructure spending is undoubtedly a good idea. But we don’t need to change the monetary system to achieve it. The public sector can do what it has always done and issue bonds to finance expenditures. (This sentence will inevitably raise the ire of the Modern Money Theory crowd, but I don’t want to get sidetracked by that debate here.)

Further, the conflation of QE with the use of newly printed money for government spending is another example of sleight of hand by Positive Money. QE involves swapping one sort of financial asset for another – the central bank swaps reserves for government bonds. This is a different type of operation to government investment spending – but Positive Money present the case as if it were a straight choice between handing free money to banks and spending money on health and education. It is not. It should also be emphasised that printing money to pay for government spending is an entirely distinct policy proposal to full reserve banking – which do would nothing in itself to raise infrastructure spending – but this is obfuscated because PM labels both proposals ‘Sovereign Money’.

The same is true of other issues raised by PM: inequality, excessive debt, and financial instability. All are serious issues which urgently need to be addressed. But PM is wrong to promise a simple fix for these problems. None would be solved by full reserve banking – on the contrary, it is likely to exacerbate some. For example, by narrowing the focus to the deposit-issuing banks, PM excludes the rest of the financial system – investment banks, hedge funds, insurance companies, money market funds and many others – from consideration. The relationship between retail banks and these ‘shadow’ banking institutions is complex, but in narrowing the focus of ‘financial stability’ to only the former, the PM proposals would potentially shift risk-taking activity away from the more regulated retail banking system to the less regulated sector.

Another justification PM provide for full reserve banking is that issuing money generates profits in itself. By stripping the banks of money creation powers, the government could instead gain this profit (known as ‘seigniorage’):

Government finances would receive a boost, as the Treasury would earn the profit on creating electronic money, instead of only on the creation of bank notes. The profit on the creation of bank notes has raised £16.7bn for the Treasury over the past decade. But by allowing banks to create electronic money, it has lost hundreds of billions of potential revenue – and taxpayers have ended up making up the difference.

This is incorrect. As explained above, banks make a profit on the ‘spread’ between rates of interest on deposits and loans. There is simply no reason why the act of issuing money generates profits in itself. It’s not clear where the £16.7bn figure is taken from in the above quote since no source is given. (While Martin Wolf appears to support this position, he instead seems to be referring to general banking profits from interest spreads, fees etc.)

None of the above should be taken to imply that there are not problems with the current system – there are many. The banks are too big, too systemically important and too powerful. Part of their power arises from the guarantees and backstops provided by the state: deposit insurance, central bank ‘lender of last resort’ facilities and, ultimately, tax-payer bailouts when losses arise as a result of banks taking on too much risk in the search for profits. QE is insufficient as a macroeconomic tool to deal with on-going repercussions of the 2008 crisis – government spending is needed – and has pernicious side effects such as widening wealth inequality. The state should use the guarantees proved to the banks as leverage to force much more substantial changes of behaviour.

Milton Friedman was a proponent of the original Chicago Plan, and the intellectual force behind the monetarist experiment of the early 1980s. He was also deeply opposed to Roosevelt’s New Deal – a programme of government borrowing and spending aimed at reviving the economy during the Great Depression. Friedman describing the New Deal as ‘the wrong cure for the wrong disease’ – in his view the problems of the 1930s were caused by a shrinking money supply due to bank failures. Like PM, he favoured a simple monetary solution: the Fed should print money to counteract the effect of bank failures.

He was wrong about the New Deal. But his description is fitting for Positive Money’s Friedman-inspired monetary solutions to an array of complex issues: lack of decent jobs, inequality, financial instability and environmental degradation. The causes of these problems run deeper than a faulty monetary system. There are no simple quick-fix solutions.

PM wrongly diagnose the problem when they focus on the monetary system – so their prescription is also faulty. Full reserve banking is the wrong cure for the wrong disease.

It’s probably worth mentioning, because it is always forgotten, that bankers are people and they spend and consume too. So interest is returned to firms via the spending channels. The Interest paid on loans, less the little they give to depositors if any, is merely the wages of bankers. And that wage is paid because the job of a banker is to decide who gets widely acceptable credit and who doesn’t.

If you take that job away from bankers, then it still has to be done by somebody. They would then be a public servant and receiving a wage from the state instead of the bank. So the PM argument is merely one of how you decide who gets money and who gets the money. They prefer a highly centralised solution controlled by a cabal of the elite (people like them in other words) who decide how much money the economy needs by some mystical process that has as much chance of working as reading tea leaves.

So it’s really just monetarism wrapped in a pretty PR shell.

LikeLike

This is of course true. But don’t you have to add that private banking is also making profits for the owners of the banks? While a form of state-driven form of banking would be able to only cover the cost of hiring bankers without having to make profits? I am not arguing for or against this.

Another thing, if we had state-driven banks they might work under more ‘democratic’ criteria than those the private banks chose to function under. State owned banks might have a mandate of working for the public good with detailed descriptions of criteria for making loans.

Needless to say such a form of state run bank system would also create faults and problems etc. But I guess it comes down to which kinds of criteria, problems and faults one prefer. And that should be a political problem. Not held outside political discussion.

LikeLike

I’m pretty sure the workers in the bank don’t see most of the profit. So I guess their wages only help recurculate a small portion of the profit. Most of it probably goes into the financial markets (where they don’t create real value).

LikeLike

While I consider Positive Money to be snake oil salesmen, and I do agree that the money system is not the cause of environmental degradation, this article is factually incorrect about their proposals. The Positive Money proposal is for sovereign money, not full reserve banking. That means that the banks effectively manage transactions money on an agency basis, not on their balance sheet.

LikeLike

To judge by Neil Wilson’s above comment, he doesn’t know very much about Positive Money proposals. First, he says “So the PM argument is merely one of how you decide who gets money and who gets the money. They prefer a highly centralised solution controlled by a cabal of the elite….”.

As regards “who gets money” in the sense “who gets loans”, that is decided under full reserve banking very much as it is now: that is it is up to individual banks or “lending entities” to decide who is credit-worthy and who gets loans. The only difference is that under full reserve, lending entities are funded by equity and similar (e.g. bonds that can be bailed in) rather than by deposits.

Second, and as regards matters macro rather than micro, Neil objects to a “cabal of the elite” deciding how much extra money the economy as a whole gets when stimulus is needed. Well there is a teensy problem there, namely that the size of a stimulus package is already decided by a “cabal of the elite” under the existing system!! That is, the size of any fiscal stimulus package is decided by finance ministers guided in the case of the UK by the Office for Budget Responsibility. As to interest rate adjustments, that’s decided by a Bank of England committee.

However (as Scott Sumner is forever pointing out), so called “independent” central banks have the power to overried what they see as excess or deficit stimulus coming from fiscal sources, thus stimulus under existing arrangements is decided by a truly horrendous (according to Neil Wilson) and very small “cabal of the elite”, namely central bank committees.

LikeLike

Good for you to recognize that banks are both creators of money at origin and intermediaries. The largely heterodox inspired argument that banks are not intermediaries is quite bogus. Tobin understood all this and the rest in 1963.

I think the rest of your argument slides a bit off the essential rail, although it contains large elements of truth in fact. The core explanation should be that in a simple model, where the level of loans is assumed fixed (temporarily), the spread earned by the banks results in a destruction of deposits and the creation of bank equity. It’s a simple accounting transfer on a net basis. Intuitively, that’s how the banking public pays for the services of banks – with the net destruction of money. So from a common sense perspective, that is at least mildly contractionary at the margin. It doesn’t take a monetarist to appreciate that. If the banking system isn’t expanding in size, then banking profits are sucking out money into bank equity. Something has to give. That’s also intuitively why banks tend to start not making much money when the economy stalls. So there’s a small element of truth in what the positive money people are saying, but I wouldn’t give them credit for understanding the correct argument. A lot of the other things you say can be added around that core recognition, but I think that’s what lies at the center of it.

The essential problem here is the most people, including most economists, don’t understand the facts of basic accounting that reflect the facts of operations. This general mistaken idea that there is a problem of where the interest “comes from” reflects a failure to understand that.

BTW, I’ve never seen an explanation or a version of the Chicago Plan that includes decently coherent accounting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

although dividends typically at least partially reverse that money destruction

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes – dividends would be my first response to the point above. As you probably know, there’s a very long-run controversy in economics called the ‘Profit Puzzle’. This is essentially what you describe above (although it is wider than an issue of bank profits alone). See e.g. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/20371/1/Source_of_Profit_Tomasson_and_Bezemer.pdf

I have a take on this – I’ll write it up in a separate post at some point.

LikeLike

Jo Michell: Full reserve is about having reserves, right? – but Positive Money’s solution is not about full reserve. Bank can lend out all their money – with no reserves. When banks can’t create money (only the central bank can) they don’t need reserves – because they don’t “pretend” to have money, so the money is either there or it isn’t. No “backup” reserves for bank-run needed 🙂

LikeLike

Jo Michell: Full reserve is about having reserves, right? – but Positive Money’s solution is not about full reserve.

In PM’s solution Banks can lend out all their money – with no reserves. When banks can’t create money (and only the central bank can) they don’t need reserves – because they don’t “pretend” to have money, so the money is either there or it isn’t. No “backup” reserves for bank-runs needed 🙂

LikeLike

“BTW, I’ve never seen an explanation or a version of the Chicago Plan that includes decently coherent accounting.”

Maybe you should try looking?

LikeLike

Another major problem with 100% reserve banking is that it abolishes maturity transformation.

Look forward to seeing your thoughts on the profit paradox / puzzle. You should have an answer which doesn’t rely on deficits or credit…

LikeLike

The fact that 100% reserve abolishes maturity transformation is a complete non-problem. Reason is thus.

All maturity transformation does is to create liquidity / money. Given that the state can create limitless amounts of money at the press of a button, the abolition of maturity transformation is no problem. Moreover, as Douglas Diamond put it in the abstract of a paper of his (link below) private banks only manage to create liquidity / money by increasing the likelihood of bank runs.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w7430

LikeLiked by 1 person

There have been several times in history when money was printed out of thin air for the people by the central banks, not the banks. WWI English banks were doomed as some of their biggest customers defaulted – the new enemies, Germany, Ottoman empire and Austro empire. The central bank bought the non performing loans and made it possible to finance a war effort – and avoid a credit panic! Japan after WW2 was in an even worse situation and the central bank had the same solution, 2008 was similar. So why not have the central bank buy government bonds and permit the appropriate amount of infrastructure and military spending and have full employment as Friedman et al had sought?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Clearly the author has not read the Positive Money position. Instead he has set up his own straw man to beat up on. Sovereign money is not “full reserve banking”. Since the author doesn’t seem to have the time to Google what sovereign money really is, hear’s a link:

http://positivemoney.org/2017/04/sovereign-money-is-not-full-reserve-banking/

LikeLike

“…money is destroyed when loans are repaid.” I believe this notion to be false. Here’s why:

If Jill were to take out a loan from the bank, the bank would make the loan, thereby “creating new money.” If Jill were to subsequently pay back the loan directly from her deposit without taking any other action, the bank would then have 100 in cash that it didn’t have before the loan took place. The money would not be destroyed, but likely deposited at the Fed, thus expanding the bank’s reserves. The end result would be the same if Jill made other transactions in the interim before paying off the loan. The missing piece on the balance sheets is the asset that Jack had that Jill bought.

This is just what I observed while following the logic of your argument. I would appreciate your feedback.

LikeLike

I’m sure this is embarrassingly basic but — I keep getting hung-up at: “When a bank lends £100 to a customer, both ‘loans’ and ‘deposits’ increase by £100”. I don’t see why a loan BY Bank A necessarily results in an equal deposit AT Bank A. NOTE: I do understand that (except in the illogical case that the loan is stuffed under a mattress) any loan ultimately works its way through transactions and ends-up in a Bank account, or in several Bank accounts, owned by one or more people — but not necessarily in an account, or accounts, at Bank A. Can someone enlighten me? Thanks

LikeLike